Marine Biology, Chemistry Undergrads Collaborate to Publish Pioneering Research on Marine Aquarium Trade Practices

Through work on real-world research, “RWU excels at providing meaningful engagement, and our students' publications are a testament to that commitment,” said Andrew Rhyne, Professor of Marine Biology.

BRISTOL, R.I. – As undergraduate students at Roger Williams University, Julia Dwyer ’22, Marion Olsen ’22, and Elizabeth Sanford ’22 worked alongside Professor of Chemistry Nancy Breen and Professor of Marine Biology Andrew Rhyne to conduct interdisciplinary research on cyanide exposure in marine fish in an effort to help curb illegal fishing practices. This year, their pioneering research was published in a leading scientific journal and demonstrated how the powerful combination of Marine Biology and Chemistry can lead to novel solutions for complex environmental challenges.

Their study, “The half-life of cyanide in the blood of the marine fish, Amphiprion clarkii after cyanide exposure,” which was published in the Bulletin of Marine Science in June, holds the potential to greatly enhance global initiatives aimed at curbing illegal fishing practices like cyanide fishing and demonstrates.

"It's quite rare for undergraduates to engage in high-level research opportunities like these. At RWU, our focus on undergraduate education ensures that students can participate in such significant projects, which they might not access elsewhere,” Rhyne said. “RWU excels at providing meaningful engagement, and our students' publications are a testament to that commitment. It's one thing to conduct research, but it’s an entirely other thing to actually have it published.”

Building on a 2021 study published by PeerJ that proved that blood tests are possible to determine cyanide exposure, this most recent study is another significant milestone in the team's pursuit to combat cyanide fishing, a practice prevalent in the Indo-Pacific region, which involves releasing cyanide into the water to poison fish, making them easier to catch for the live fish food and marine aquarium trades. Fish subjected to cyanide suffer significant physiological stress and degradation, and the subsequent handling and transport through lengthy supply chains further intensify their suffering, leading to high mortality rates. The environmental consequences are equally severe, as the process often leads to extensive damage on the ocean floor that renders these habitats incapable of supporting diverse marine life.

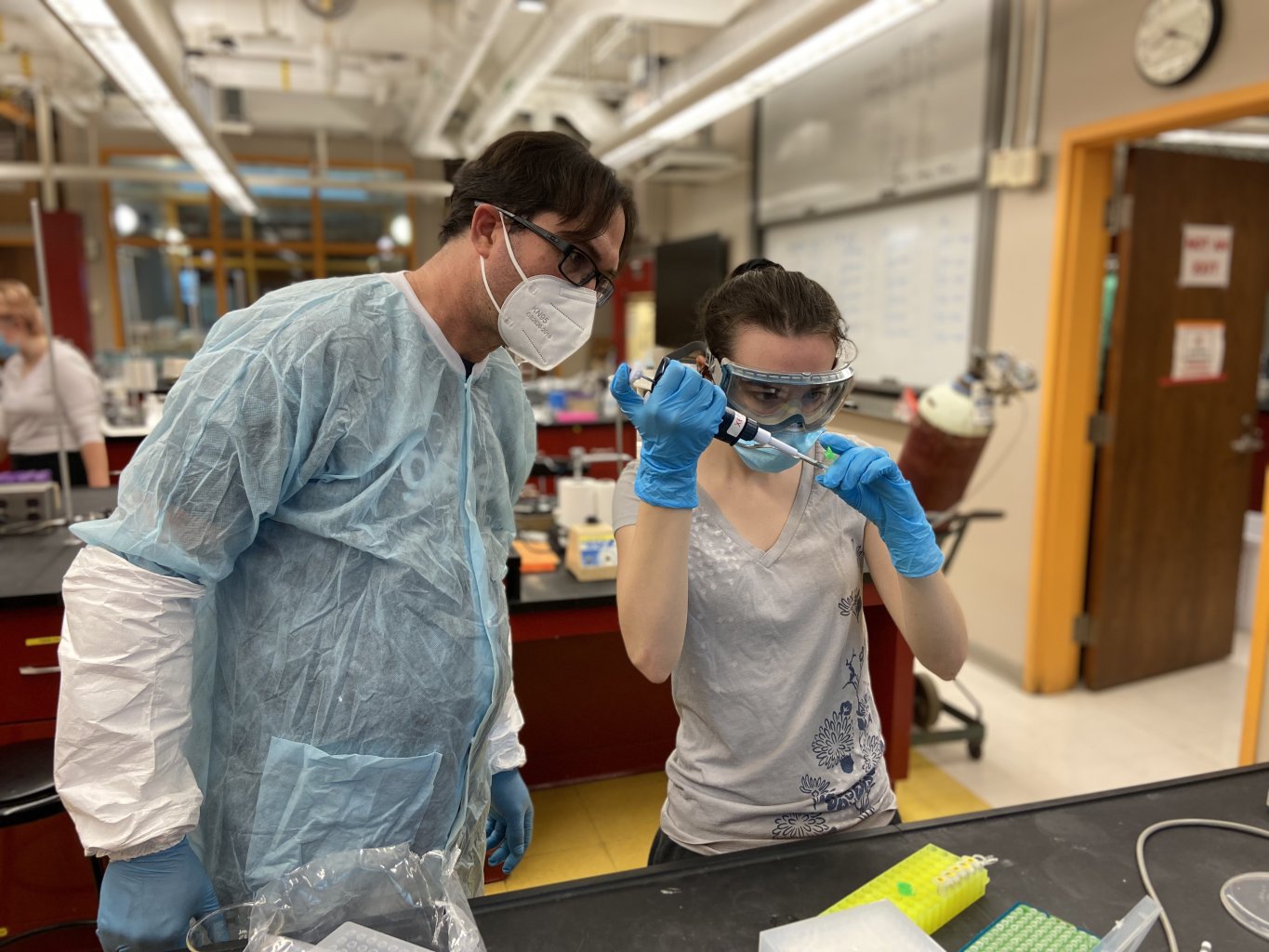

Over the past decade, Breen, Rhyne, and their team of undergraduate researchers have aimed to develop a reliable tool that empowers exporters and countries to monitor and eradicate cyanide fishing. By providing a scientifically validated method to detect cyanide in fish, RWU researchers are working toward ensuring sustainable fishing practices and the protection of marine ecosystems worldwide.

Through Research Opportunities, Students Develop the Skills to Soar

RWU undergraduates have hands-on learning opportunities that rival those typically reserved for graduate students. At the forefront of groundbreaking research and with the support of faculty mentors who are experts in their fields, students like Dwyer, Olsen, and Sanford can earn their first published credentials through undergraduate research and help advance scientific knowledge by applying their academic studies to solve real-world problems.

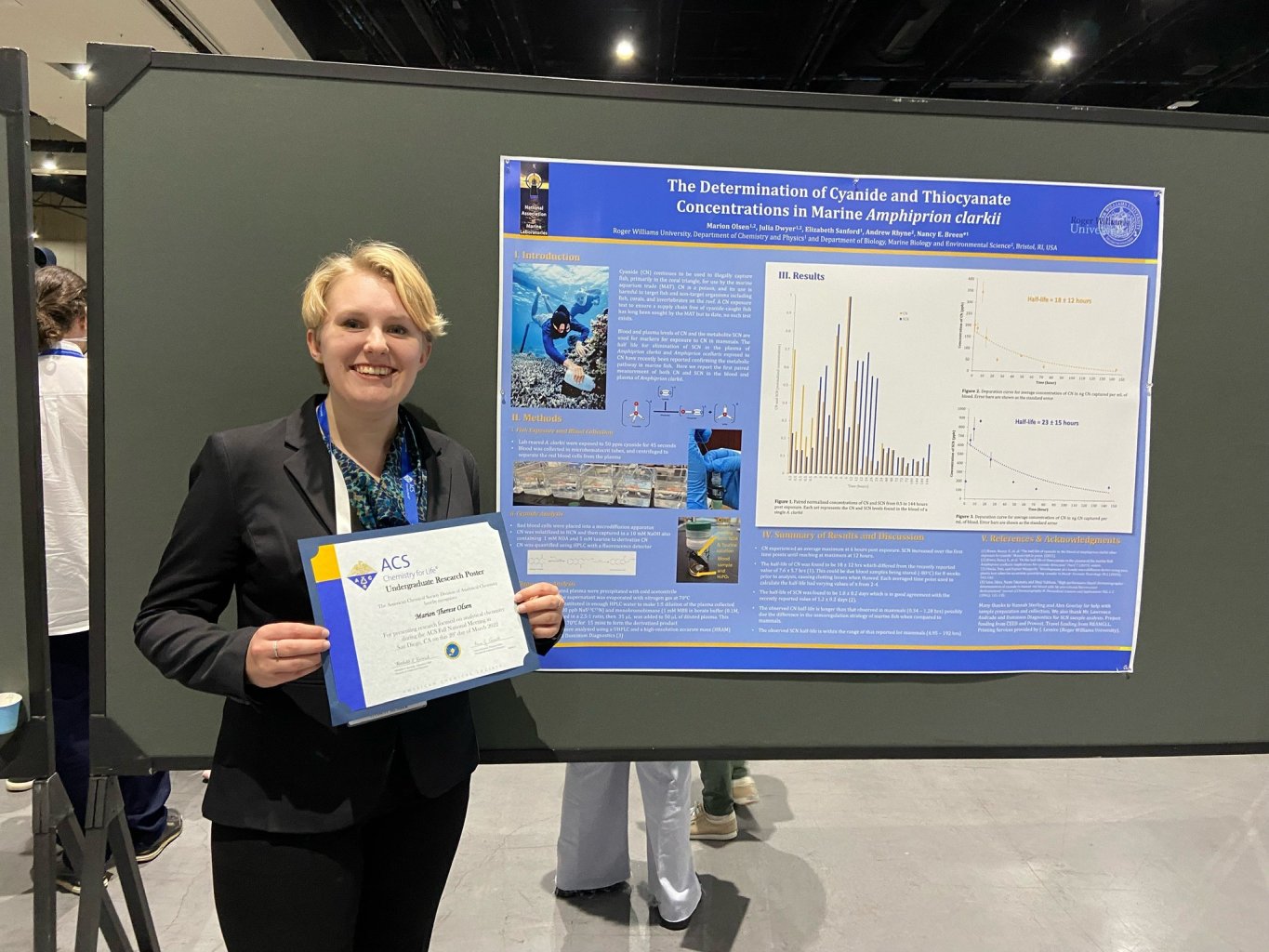

Breen and Rhyne bring invaluable expertise and support to their roles as mentors, guiding numerous students through the rigors of undergraduate research. As part of their latest exploration into cyanide exposure, more than a dozen students contributed their efforts to both the experimental procedures and animal husbandry, with Dwyer, Olsen, and Sanford presenting their research at the Analytical Chemistry Division of the National Meeting of the American Chemical Society in San Diego. They shared that these experiences allowed them to develop the critical thinking and problem-solving skills essential for future academic and professional success.

For Sanford, who graduated with a bachelor’s in Chemistry and currently works as a research and development analytical chemist for DuPont, the skills gained through undergraduate research set her up for success in a competitive profession.

“Not only does undergraduate research at Roger Williams University enhance your application to graduate schools, but it also significantly boosts your prospects in the job market,” Sanford said. “I was able to claim this project as two years of experience with analytical chemistry, which really helped me stand out among other candidates who only had a chemistry degree. The hands-on research opportunities here are a major reason why RWU stands out from other institutions.”

Olsen, a medical technologist at KBMO Diagnostic in Hopedale, Mass., highlighted how her bachelor’s degrees in Biology and Chemistry were instrumental in her post-graduation career.

"It was an amazing opportunity, and I'm so grateful that I got to work on such an exciting research project with good friends,” Olsen said. “I'm certain the reason I got into my Ph.D. program was because of this research. It taught us so many things and opened doors for our careers. We wouldn’t have gotten nearly as far without it."

Bridging Disciplines for Groundbreaking Research

Breen emphasizes the transformative nature of interdisciplinary research, noting how it opens doors for students to explore subjects beyond their primary area of study and enriches their academic experience.

“These interdisciplinary collaborations are the best parts of science, allowing students to bridge different worlds. A Marine Biology student might not initially be interested in a lab process involving blood samples and cyanide detection, but understanding the broader context and impact of their work can engage them in the chemistry, biochemistry, and toxicology involved,” she said.

For Rhyne, this approach is a hallmark of the broader scientific community and offers students invaluable real-world experience. “Often in science, you’re integrating two or three different fields to gather valuable data, which is crucial for solving real-world problems,” he said. “This is why I love working with students who have an interest in chemistry or a strong enough background to pursue double majors; it makes them better and more well-rounded professionals with the expertise to develop comprehensive and innovative solutions.”

The student researchers' backgrounds in Biology, Chemistry, and Marine Biology were pivotal in the success of their project, each bringing distinct expertise. Olsen and Sanford both played critical roles in the chemistry side of the study, including optimizing and troubleshooting the process for detecting cyanide. Dwyer, who received bachelor’s degrees in Chemistry and Marine Biology, and now works alongside Olsen as a medical technologist at KBMO Diagnostic, ensured that the analytical techniques were adapted to the complexities of studying cyanide exposure in marine fish.

“I loved this research project because it combined both of my majors, allowing me to engage deeply with both marine biology and chemistry and view things from various perspectives,” Dwyer said. “It was an incredible opportunity to start from the beginning of a project and see it through to the end, and the experience I gained was rewarding and invaluable.”

Opportunities Continue for Student Researchers

As Rhyne and Breen continue their research into this topic, one significant direction involves extending the research to other fish species, particularly larger ones from which multiple blood samples can be drawn, as well as exploring the physiological differences between freshwater and saltwater fish. They said they are also particularly interested in identifying genetic markers that could indicate cyanide exposure over a longer period, with the goal of developing a practical test to reliably detect cyanide exposure. Their next phase of research will involve a new cohort of student researchers, bringing fresh perspectives and skills to build on the team's trailblazing discoveries.

For Dwyer, Olsen, and Sanford, the journey has been transformative, deepening their commitment to marine conservation. Working closely as a team, they became passionate advocates for sustainable practices, gaining invaluable experience that they said will drive their future research and professional endeavors.

“Roger Williams University's location by the ocean and its focus on marine life made this project especially meaningful,” Sanford said. “It was eye-opening to uncover the destructive practice of cyanide fishing used to capture fish for the aquarium and food trades. Being part of this crucial conversation about protecting marine environments and contributing to efforts aimed at ending such harmful practices was truly inspiring, and we made groundbreaking discoveries that will undoubtedly advance research in the field.”